FIRLAND SANATORIUM’S FINAL SOLUTION FOR SEATTLE’S WHITE PLAGUE

“Vile Criminals” and “Degenerates” were incarcerated in what is now a private Christian school

by Brian Platt

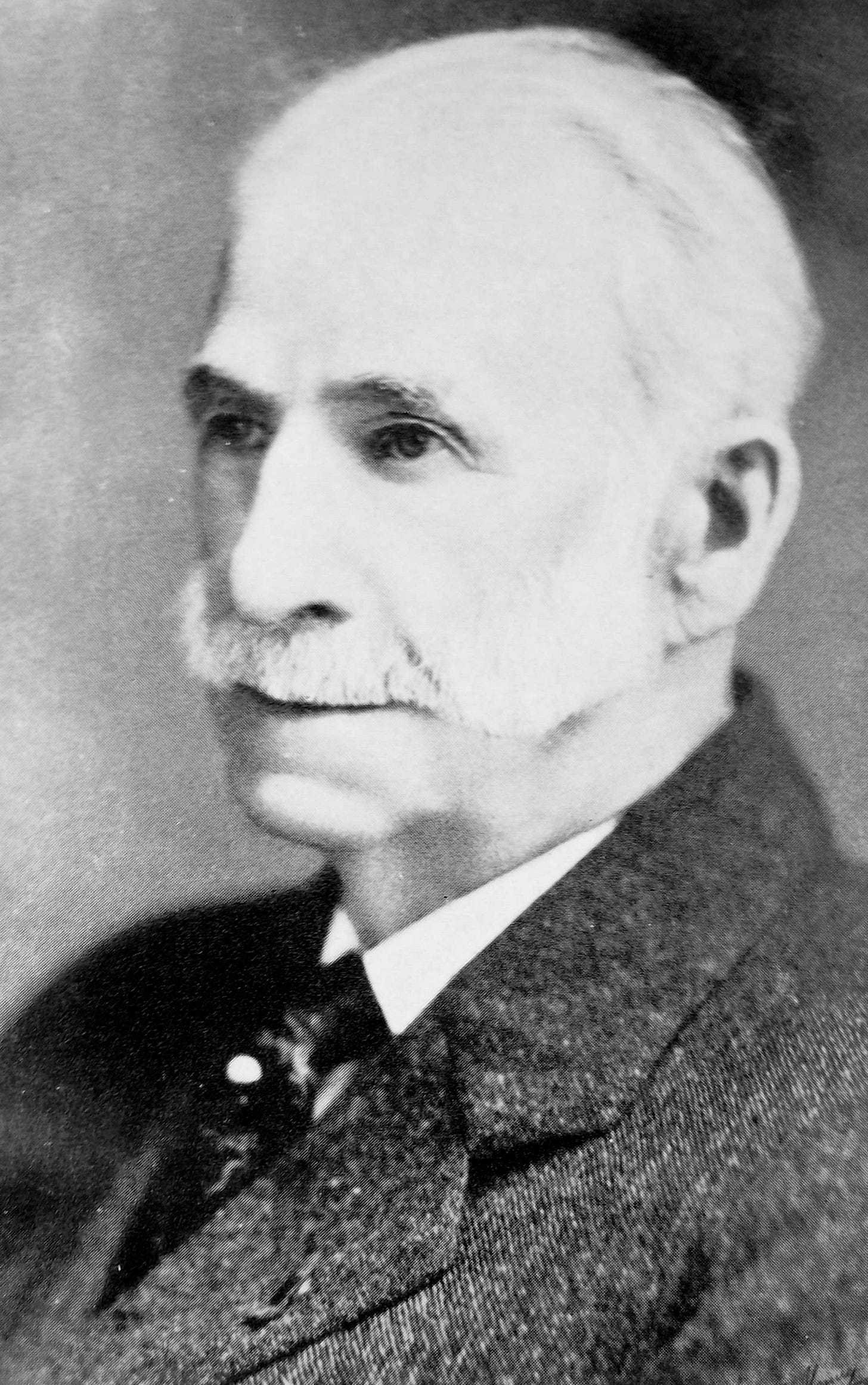

“The people, as a rule, do not appreciate the facts in the case,” the new head of the Seattle health department, James Crichton, warned the readers of his Health Bulletin in 1909. They “are not educated up to the point of considering the maintenance of public health as a business proposition. But it is a business proposition, as an investigation of the facts will easily disclose.”

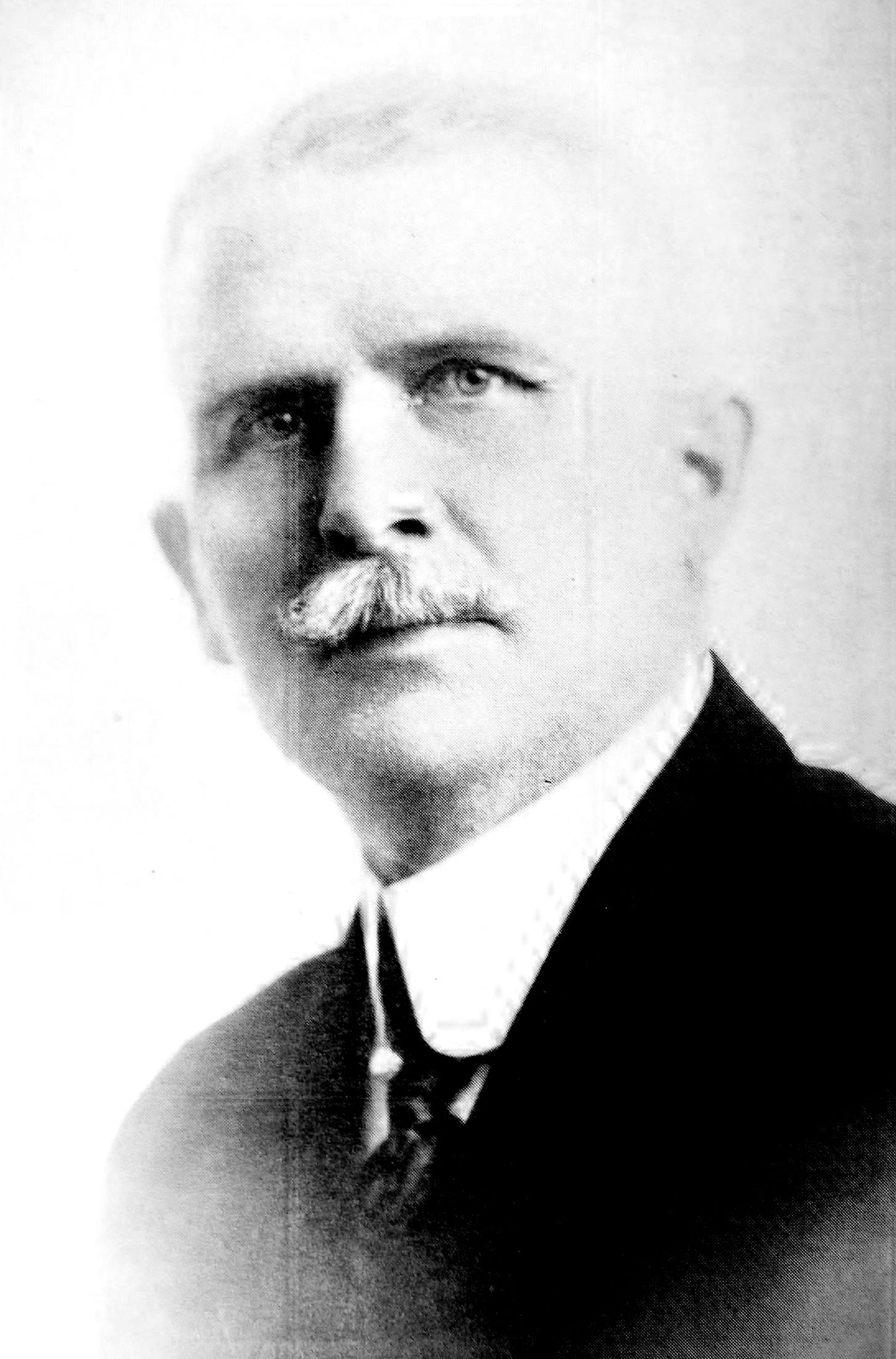

Appointed in the aftermath of an outbreak of bubonic plague, Crichton was charged with cleaning up the city ahead of its great coming-out party, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYPE) in 1909.

“How a public marvel like Firland became an exclusive religious prep school, is the story of how capitalism tried to use public health to solve the urban crisis, and then, abandoned it.”

A product of the Progressive Era, with its emphasis on expertise and scientific management, Crichton promised to create a “new type of socially enlightened statesmanship” to solve the social ills of the city. In 1914, the crown jewel of this enlightened statesmanship, Firland Sanatorium, opened on a plot of land just north of Seattle. It was the city’s first tuberculosis hospital and it was praised by the Seattle Times as “one of the finest and most useful municipal establishments of its kind in the world.”

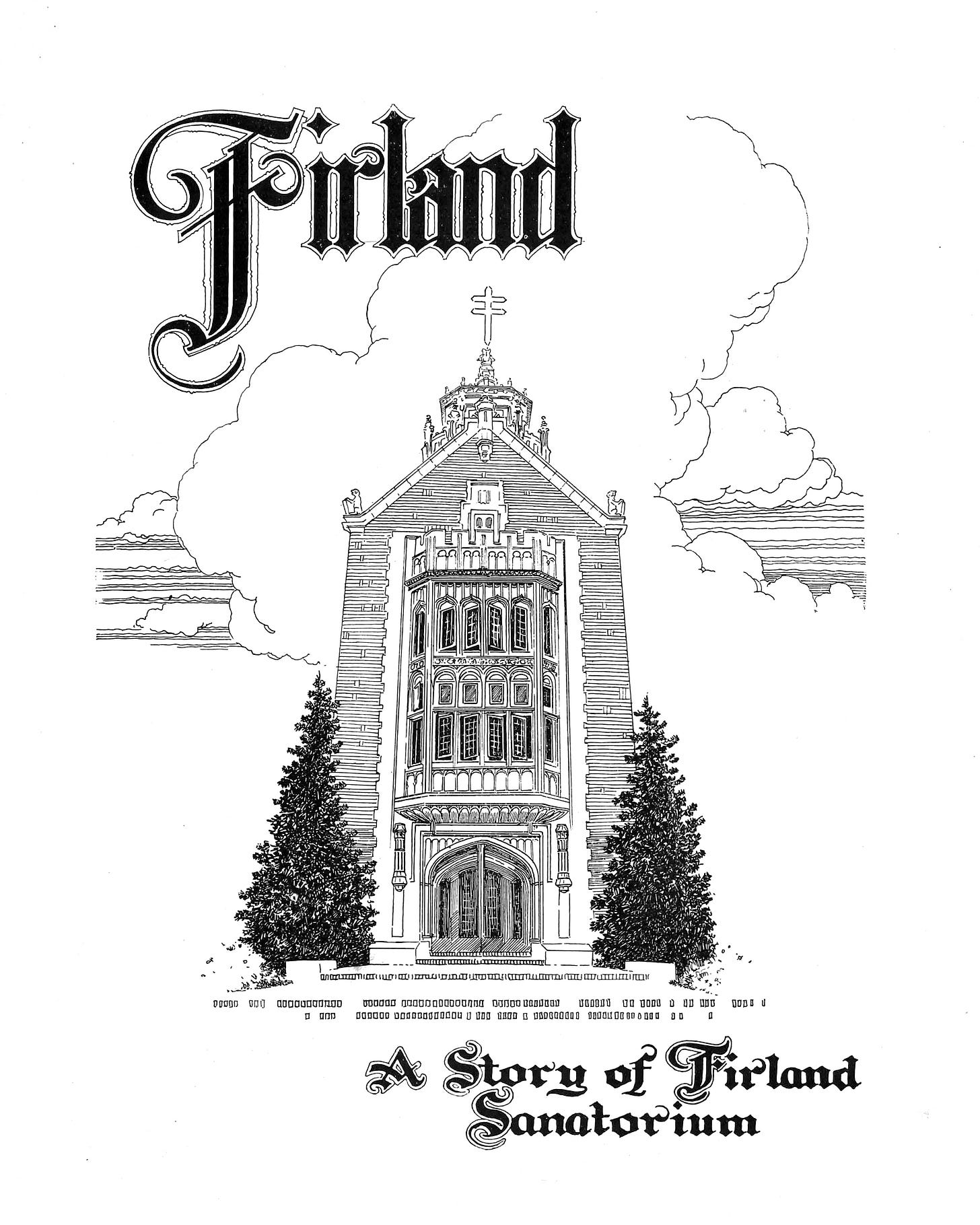

Today, many of Firland’s buildings still exist, including the much touted at-the-time administration building and powerplant, only they are now part of King’s School – a private school that promises the “priceless gift of a Christian education” for the low cost of twenty-thousand dollars a year (plus fees). How a public marvel like Firland became an exclusive religious prep school, is the story of how capitalism tried to use public health to solve the urban crisis, and then, abandoned it.

The Urban Crisis

To understand why Firland was built, we must revisit the Seattle that James Crichton knew. With the discovery of gold in Alaska, the population of Seattle exploded from forty-thousand in 1890 to more than two-hundred-thousand people in 1910. Seattle’s unique geography provided for a strict class and racial segregation. The wealthy moved first onto First Hill, then into Queen Anne and Capitol Hill, before finally moving to the Highlands – Seattle’s first gated community located a mile south of King’s School. As the city’s oligarchs moved higher up into the hills, the burgeoning professional class filled in the elevations just below them.

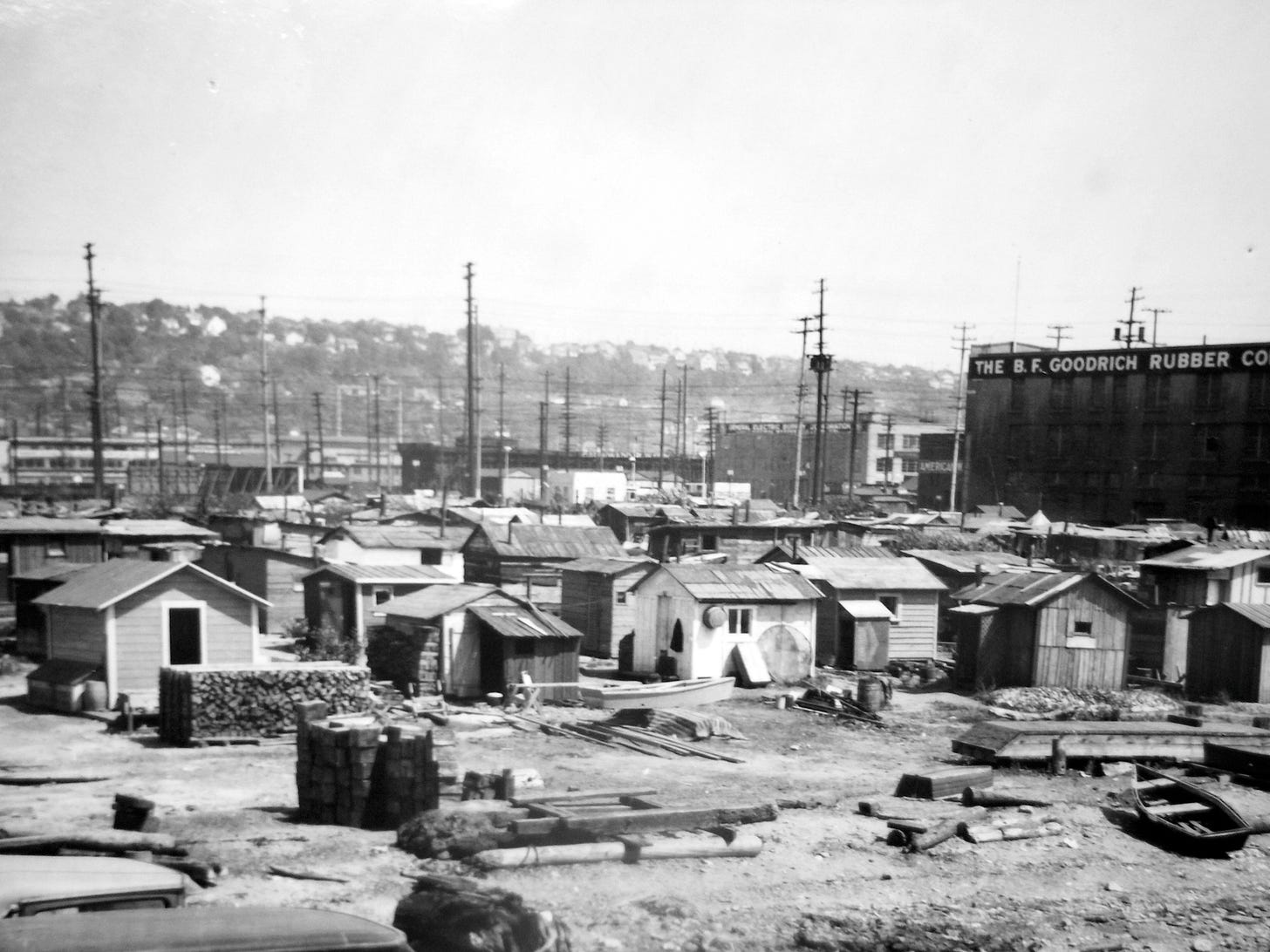

At sea level, where the stadiums now reside, the tide flats were reserved for the shacks of the city’s vast and growing army of itinerant workers. Made up primarily of loggers, fishermen, gold prospectors, and mill workers, these slums were the product of the city’s low wages and highly volatile as well as seasonal industries. The largest settlement, known as Shacktown, boasted more than 1,200 improvised shacks, housing around 3,500 people by 1913.

The workers that filled Seattle’s slums were reviled by the members of polite society and all the aspirants that aspired to one day move further up the hills around the city. Indicative of this feeling, a front page story in the Times described Shacktown’s residents as “a wretched community of animalism” where “Siwashes, negroes and degenerate whites herd together in these hovels and are producing a race which some day will be a heavy menace to the city.”

While it was true that Seattle’s slums were the only racially integrated neighborhoods in the city, the residents of Shacktown vehemently denied the Times’ “damnable lies” about their criminality and shiftlessness and dragged a reporter from the rival Seattle Star down to the tide flats to see for himself.

The reporter noted that the wages from working twelve-hour days in a Seattle mill did not leave one much to live on while leaving many workers physically crippled in the process. Still, the article in the Star stands out primarily for its uniqueness, as the general tenor in the city tilted toward the hysterics of the Times.

A Times exposé of a different Seattle shanty town a year later probably hit closer at what truly bothered the paper about the urban poor. In it, the Times lamented that these slum dwellers would dare live “where property values are the highest and where thousands of people rich in this world’s goods pass daily.”

And this was the heart of the urban crisis that afflicted Seattle’s wealthiest citizens. They could move up the hills away from downtown; they could hire the Olmsteads – of Central Park fame – to build them a series of public playgrounds out of reach of the city’s urban poor; they could erect an armory to act as a sentinel between the wealthy neighborhoods of the north and the city’s slums to the south. But they still had to come into downtown to conduct business. Once there, they were forced to share the urban space with the workers that they despised so much. Faced with growing inequality, Seattle’s well-off asked themselves the eternal question, “How can we get rid of all these poor people.”

Public Health and Poor Removal

City ordinances were passed to try and curb the habits of the urban poor, but it was the health department that would ultimately take the lead in poor removal. Beginning in 1908, Crichton began an aggressive strategy of sweeping the shanty towns around the city. The involvement of the health department in poor removal was an outgrowth of the assumption that poverty, disease, and contagion were interlinked. In its reporting, the Times referred to Seattle’s slums as “a hotbed of disease, contaminating the entire neighborhood” and assured its readers that the health department was being mobilized to remove the disturbance.

The connection between poverty and disease was, of course, not without a kernel of truth. Tuberculosis, the leading killer in Seattle at the turn of the century and the great white whale of its health department, can be said to be caused by the mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli. Yet, the tuberculosis bacterium is incredibly prevalent in human populations. In the 19th century, it’s believed that 1-in-3 people had it, yet many remained asymptomatic. For tuberculosis to manifest as the illness that earned the moniker “the white plague,” an infected person must also be exposed to environmental conditions that weaken the immune system.

Pollution, exhaustion, and malnutrition all can lead to the manifestation of tuberculosis. Seattle’s slums abutted the city’s shipping and factory districts. The coal dust from these industries had to be swept daily from the houses in Shacktown. Malnutrition and exhaustion were the wages of the city’s open-shop policy. As such, tuberculosis proliferated among the city’s working poor.

The connection between exploitation and disease was no secret at the time. The Union Record reported that “bad industrial conditions” in the city’s shingle mills were the cause of “cedar asthma” – a sawyers’ colloquialism for tuberculosis – and was “directly responsible for the high mortality among workers.” A state factory inspector told the Times in 1910 that a lack of labor regulation meant that many women worked 60-70 hour weeks in Washington. She noted that “tuberculosis is promoted by overwork as much as by any other single cause” and concluded, “There is a more practical way of fighting this disease. To shorten the hours of daily work to afford daily leisure for rest and recreation.”

This was not a solution that the city’s capitalist class was interested in. Before becoming health commissioner, James Crichton was a practicing medical doctor and the longtime city council representative for Queen Anne – he even served a brief stint as acting mayor of Seattle in 1898. Crichton preferred to see tuberculosis as a personal failing. In his typical patronizing tone, Crichton warned Seattle’s working poor, “Somebody’s child, wife or husband will die because they have been careless in not attending to things which conserve health and prevent disease. Someone will camp out and will drink polluted water, unnecessarily and will die. Some mother will not screen her house, will not clean up the premises, will not clean the nursing bottle, and her baby will die.”

Back in Shacktown, residents jeered the health inspectors as they toured the slum putting eviction notices up as they went. One resident cut to the chase, shouting, “Why don’t you leave these mansions alone until after the fair? They oughter make a fine exhibit for the city beautiful.” But Crichton’s health department was serious, they razed 162 homes in 1908 alone.

Many asked where these residents were supposed to go. Women with children beseeched the city to not evict them into homelessness. A local reverend asked the city to build housing first for evicted residents rather than just throw them out onto the streets. The council member for Pigeon Point complained that, instead of fleeing the city as officials hoped, the evicted residents simply built new shacks in his adjoining district. All to no avail. For five years the health department waged a one-sided war on the city’s poorest residents. In 1913, the Times praised Crichton for wiping Shacktown from the map by burning its “miserable structures” to the ground “thus ridding the city of a slum district more serious than many cities have had to contend with.”

The Building of Firland

So, this brings us to the question of Firland Sanatorium. While the practice of the city was to chase the urban poor from neighborhood to neighborhood, destroying all their worldly possessions in the process, there remained a rhetoric of aid for the “deserving poor.” The division of those in poverty into two groups, deserving and undeserving, allowed the reformers of the Progressive Era (and today) to erect an impermeable barrier between economic and social policy. For them, poverty was first and foremost a question of personal morality. Once this was determined, the undeserving could be punished without limit, while the deserving could be rescued – provided that no “moral hazard” was created in doing so.

In practice, the rescuing was usually the subject of endless debate, while the punishment was a matter of policy. In 1909, the Anti-Tuberculosis League (ATBL) was formed in Seattle to begin plans to build a new tuberculosis hospital. A plot of land in Queen Anne was donated to the group.

This land had been originally set aside for the purpose of building a children’s hospital, but the neighborhood came out in force against it. The “sight of said crippled and deformed children being constantly before the residents in the vicinity of said hospital will be a constant source of annoyance,” complained the city’s wealthiest residents. “Under no circumstances,” they declared, “should [this hospital] be built in a choice residence portion of the City.” Indeed, one of Crichton’s last acts as the councilman for Queen Anne was to try and pass an ordinance making it nearly impossible to build a hospital in an area if it “injured” property values.

When the ATBL began moving supplies up the hill to Queen Anne, the neighborhood formed broomstick brigades to “sweep” the workers off the hill. The Ross Improvement Club promised to take all necessary legal steps “to prevent the establishing of such a consumptive colony.” “These people are needlessly frightened,” Dr. Davison of the ATBL told the Times, “and it appears to be real estate men who are stirring up all the trouble.”

After the Queen Anne debacle, land was donated to the ATBL in Tukwila. This time the mayor came out to oppose the hospital, telling the press, “Better, far, far better allow our little ones to enter a den of raging lions than to allow that colony to exist on the outskirts of our fair and growing municipality.” Tukwila’s government expressed sympathy for those that suffered from tuberculosis, but moved to block any building that would result in “a great deterioration in property values.” A subsequent effort to build a facility on Beacon Hill met a similar fate.

It required the intervention of financier and railroad contractor, Horace Henry, to break the deadlock. Henry’s son, Walter Henry, died of tuberculosis early in 1910, after being sent to a sanatorium in Arizona for treatment. Horace was likely the wealthiest man in the city at the time, but his son’s death revealed the flaws in the way the wealthy viewed disease. Poverty was seen as an individual moral failing and tuberculosis was one of that failing’s deserved punishments. Yet, the capitalist class could not wholly quarantine itself from the working class in the city. And the poor, whose wretched conditions became a prime breeding ground for the disease, in turn, became a vector for re-introducing the disease back into the ranks of the wealthy.

“How can we get rid of all these poor people.”

As historians René and Jean Dubos note in their history of tuberculosis, “The passion for financial gains made acquisitive men blind to the fact that they were part of the same social body as the unfortunates who operated their machines. Tuberculosis was… perhaps the first penalty that capitalistic society had to pay for the ruthless exploitation of labor.”

Henry, in a “Gethsemanic sorrow” over the death of his son, threw his weight behind getting the tuberculosis hospital built. He donated a leftover plot of land that he had from building the exclusive Highlands neighborhood north of the city. He then threw in twenty-five-thousand dollars for the construction of an administration building for the hospital. There was no road access to the land and supplies had to initially be brought in by wheel-barrow. The sanatorium was sufficiently far from the city to both exile the tubercular and maintain elite property values. By the end of the 1911, they had 60 patients. And in March 1912, with Henry leaning on local electeds, Seattle citizens voted to build a permanent sanatorium on that land. In June 1912 the city “took possession of the property…and Firland became the City of Seattle’s Tuberculosis Sanatorium.”

Firland’s Demise

Firland’s grand opening came in 1914, and the sight of the beautifully constructed administration building flanked by two hospital buildings on either side, along with a state-of-the-art power plant to electrify the facility thrilled onlookers. The Seattle Sun describes seeing the facility for the first time, “As the city autos rolled up on Krist Knudson’s nice brick road, the party saw shining through the trees what they thought must be a new golf and country club.”

Despite stunning at its grand opening, the city was already turning against Firland under the guise of fiscal responsibility. The Sun’s praise of Firland’s “pastoral luxury” came only as a way to damn it as “another enterprise in which a whole lot of money has been thrown away.” The Chamber of Commerce declared the hospital a “burden to the city” in its first year and demanded that further appropriations for Firland be denied in order to teach a “salutary lesson” to the city health department.

The election of Hiram Gill as mayor in 1914 dealt another blow to the hospital. Gill replaced Crichton as head of the health department with his personal physician J.S. McBride. Local press gleefully noted that McBride had “no stated policy” as regards public health beyond cutting expenditures. By March of 1915, Gill was reporting to the city council that while Firland might have a noble purpose, it was simply too expensive.

Behind the scenes, Horace Henry, began to lose the fervor for public service that had been brought on by the death of his son. Writing to Crichton in 1913, Henry argues, “considering the high rate of taxation and the temper of the people regarding it and the trying position the Council occupies I would not care for my part, at this time, to request the large amount of additional money required to complete” the remaining buildings at Firland. Henry’s change of heart was reflective of a general move toward social reaction nationally. A series of labor strikes across the East coast had the capitalist class in Seattle seeing socialists around every corner. Digging in, they demanded a program of austerity and increased policing of the city’s working class.

Still, Firland had its supporters among the city’s working class. In 1914, the Seattle Central Labor Council created a committee to go out to Firland and investigate the claims of financial impropriety that were being made by Mayor Gill and the press. The committee found no waste and called the hospital “a credit to Seattle.” The Labor Council, further, went on to recommend that the city council pass all appropriations for Firland. Continued appropriations for Firland would remain popular with the general public for the next five years.

Mayor Gill and the city council pursued a strategy of death by a thousand cuts when it came to Firland. First, the council appropriated three-thousand dollars to turn the second floor of the hospital’s power plant into a prison for “delinquent women.” The plan, cooked up with the assistance of the Seattle Police Department, was ultimately deemed infeasible.

As tuberculosis deaths in Seattle rose throughout 1915 & 1916, McBride was under pressure to expand Firland’s capacity. McBride complained that they were taking care of too many patients “in the last stages [of the disease] and [who] were financially destitute,” suggesting that care be shifted to those in the early stages of tuberculosis who could pay for their treatment and be returned to work “with the disease at least arrested.” What would happen to the dying patients? McBride did not say. Wouldn’t the healthier patients see their health deteriorate again once they went back to work? Probably, but maybe they will earn some money for another stay in the process.

McBride, the city council, and the mayor opted to try and shift the burden of paying for Firland by convincing the state to take it over. This desire to shift the burden of paying for the hospital was spurred on by the success of the Chamber of Commerce in rolling back spending. In its 1917 annual report, the Chamber bragged that it had saved taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars by opposing the “extravagance” of the city and county. The state legislature, also in an austere tax cutting mood, refused to take Firland off of Seattle’s books.

Ultimately, the event that would break the stalemate around Firland would be an event that on its face had nothing to do with public health. When Seattle unions banded together in February of 1919 and announced a general strike in the city, it sent the capitalist class into hysterics. Head of the State Defense Council, Henry Suzzalo, called the Secretary of War and asked for federal troops to retake the city. An army division was sent to occupy Tacoma and Seattle with another division waiting at Fort Lawton in reserve. Seattle’s new mayor, Ole Hanson, created his own army by recruiting six-hundred new police officers and deputizing more than two-thousand more. Fraternities at the University of Washington were deputized so that they could patrol the campus for “reds.” The Kiwanis Club handed out guns to its membership to form an armed militia. Whole page ads were taken out in every major paper demanding that labor leaders be “hanged on the nearest telephone pole” lest they turn Seattle into “the most labor-tyrannized city in America.”

In the face of such intense pressure and overwhelming force, the non-violent labor strike was abandoned after just six-days. Capitalism’s victory in Seattle made Ole Hanson a national sensation. He immediately resigned as mayor to undertake a national speaking tour as a stepping stone to getting into national politics. For the city’s working class, the end of strike was a disaster. The Central Labor Council leadership was purged and the IWW hall and the office of a socialist newspaper were raided by local, state, and federal police.

A general state of exception was declared across the country. The state legislature passed a new anti-syndicalism law as soon as they were in session, leading to more arrests. On the day the strike ended, the Times ran an editorial calling for the deportation of “alien trouble makers,” stating, “From this time forward, America will be much less tolerant than previously.” Seattle officials and local law enforcement fed information to federal police who rounded up leftists in mass dragnets and shipped them off for deportation.

In a telling-sign for the future of Firland, public health officials would again be at the forefront of state repression. It would ultimately be the Seattle health department that permanently shut down the IWW hall by declaring it unsanitary in July of 1919. James Crichton, who once saw himself as an “enlightened statesman,” now fought to keep the King County Council of Defense – a war-time “emergency measure” – active after the war to deal with “serious social and industrial unrest.” Horace Henry, the one-time champion of Firland, now devoted his time to the crusade against communism, giving speeches to community groups throughout the region.

After the strike, Firland and the ATBL changed their mission from treating the urban poor to emphasizing the treatment of children and those that could afford to pay for the extended hospital stay. The goal post for “deserving” and “undeserving” among Seattle’s working class had shifted.

Firland’s Conversion to a Private School

Firland had always been a small operation. When it opened, it had room for two-hundred patients. The paucity of beds is even more stark when compared to the more than one-thousand homes razed by the health department in the name of tuberculosis control. Despite the arson spree, urban poverty remained in Seattle. Two years after declaring Shacktown “wiped off the map,” the Times was again carrying stories of shacks on the tide flats.

As the 1920s went on, Firland existed in a state of benign neglect. Its manager, Dr. Robert Stith, dreamed of turning the facility into a European-style “garden city” – a combination sanatorium/commune. Meanwhile the capacity of the hospital was reduced to 180 beds by 1926. The reduction in capacity was papered over by racism as Stith argued that every non-citizen, Japanese citizen, and “other Oriental” who gets admitted, “keeps a bonafide citizen out of Firland.”

Dr. Leslie Lumsden, medical director of the US Public Health Service, visited Firland on a tour of Washington’s public health infrastructure in 1932. He found the state’s health department to be “obviously inadequate” and “suggestive of a skeleton organization with a number of bones missing.” He marveled that, “Notwithstanding its progressiveness in so many other important respects and its comparatively large per capita wealth, Washington State remarkably stands very near the bottom of the list of States in the provision of means for the development and maintenance of efficient (State and local) public health service.”

In 1943, Seattle was finally able to offload Firland to the county. The King County health department consolidated Firland and another county hospital and moved the patients over to an old-naval hospital – what is now Fircrest Residential Rehabilitation Center in Shoreline. At the new facility, the mission of Firland (the new hospital maintained the old name) changed. Firland’s new medical director developed a theory that tuberculosis was actually a product of alcoholism. The former naval hospital became a convenient place to kidnap and imprison indigent alcoholics for up to a year without bothering with messy issues like due-process. Shortly after moving in, the hospital’s board asked the county for money to build twenty more “cells” for alcoholics at the facility.

County officials leased the old Firland facility for one-dollar-per-year to a new religious organization, King’s Garden (now Crista Ministries), who was interested in converting it to a religious private school. For most of the 1950s, ownership of the site was tied up in a legal battle between the ATBL, the county, and various developers. The County wanted to release the land to the Shoreline School District, so that they could build a high school on it. The Municipal League and several north end clubs wanted the land converted into a park. The ATBL demanded that the land be returned to them, since the county had violated the deed by not using it for tuberculosis relief.

Ultimately, the judge decided that the land had to be sold in whole and that the proceeds, at some unspecified future date, would have to be spent on tuberculosis relief. When Firland was put up for auction in 1958, there was only one bidder, King’s Garden. King’s bought the facility for one-dollar over the one-hundred-thousand-dollar minimum bid. After a long, winding road, tuberculosis control had been converted into a scheme to disappear homeless alcoholics. And the “municipal marvel” that was Firland Sanatorium had been converted into an elite private school.

Originally published in Doomed Planet - 2026 EDITION, a 12 page newspaper.

Contact us: doomedplanetpod@gmail.com. Find the podcast at doomedplanet.com or wherever podcasts are available.